The Life of the Abbey Through Discovered Artefacts and Environment

François Blary - Anne-Marie Flambard Héricher

Images / All rights reserved

Living environment

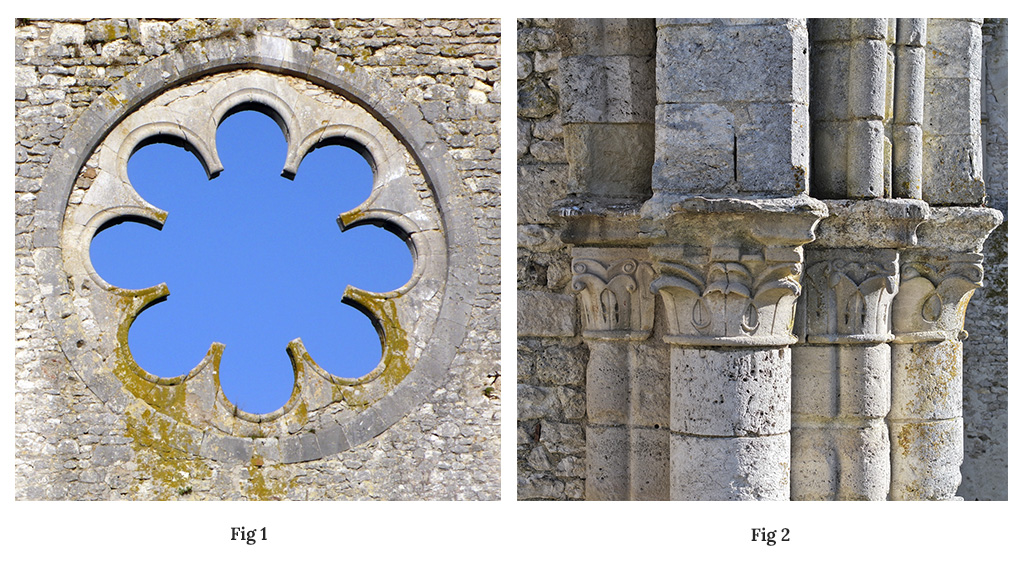

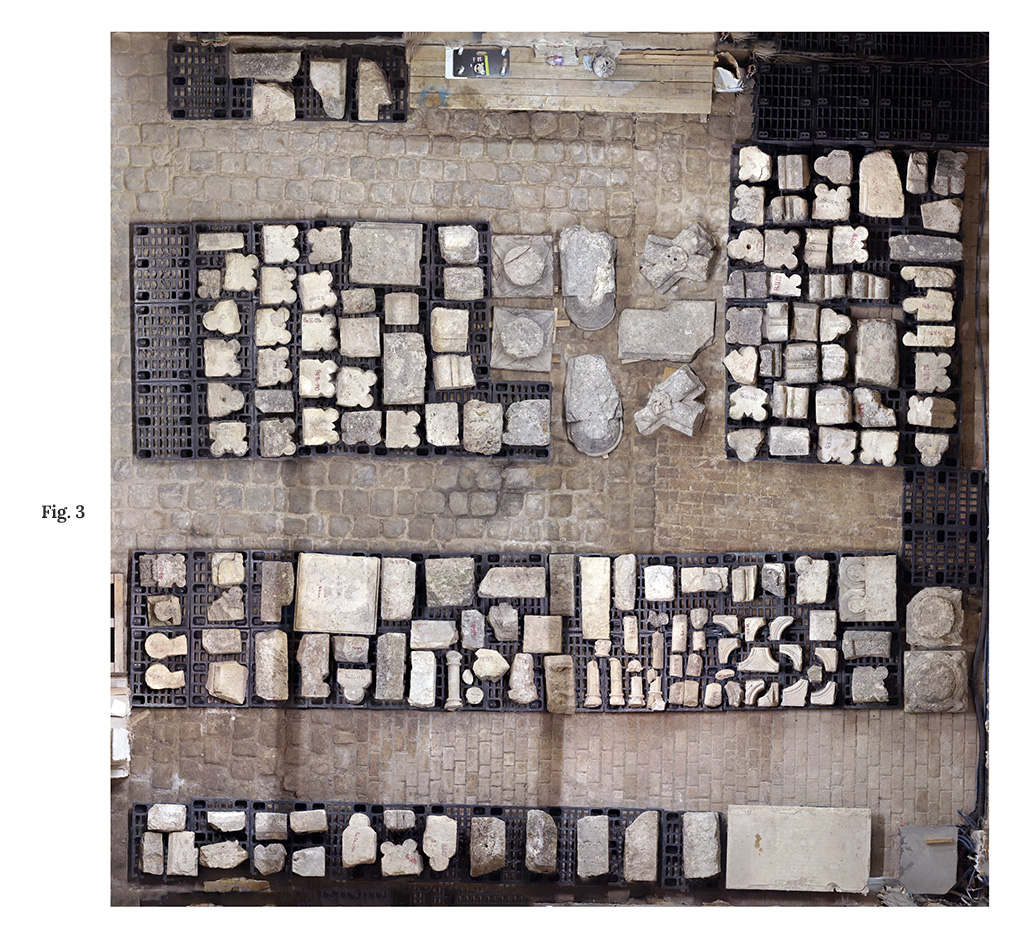

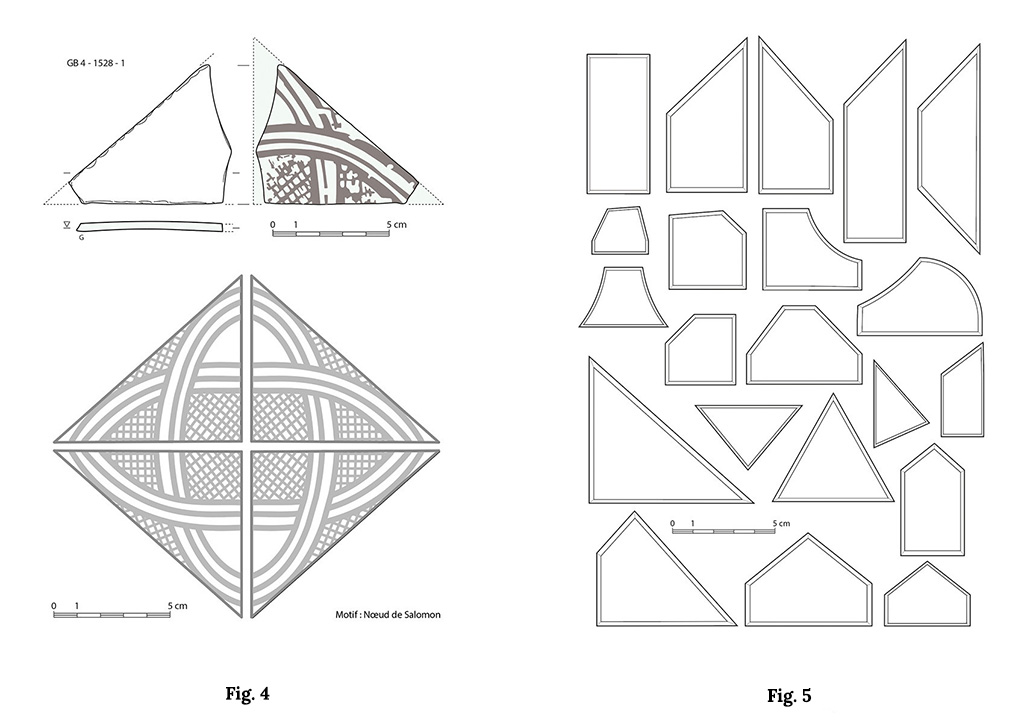

The life of the monastic community unfolded in a sober and functional setting, with discreet ornamentation. The rose window (fig. 1) and the capitals of the abbey church, preserved in situ (fig. 2) or stored in the lapidary collection (fig. 3), reflect this aesthetic.

The same care was given even to the humblest work-related buildings. The vaulted rooms of the Grange des Beauvais, for instance, featured stained glass decorated with geometric figures and grisaille patterns, set in lead strips (figs. 4 and 5).

The floors were paved with terracotta tiles—mostly plain, though some were glazed or decorated with patterns (fig. 6).

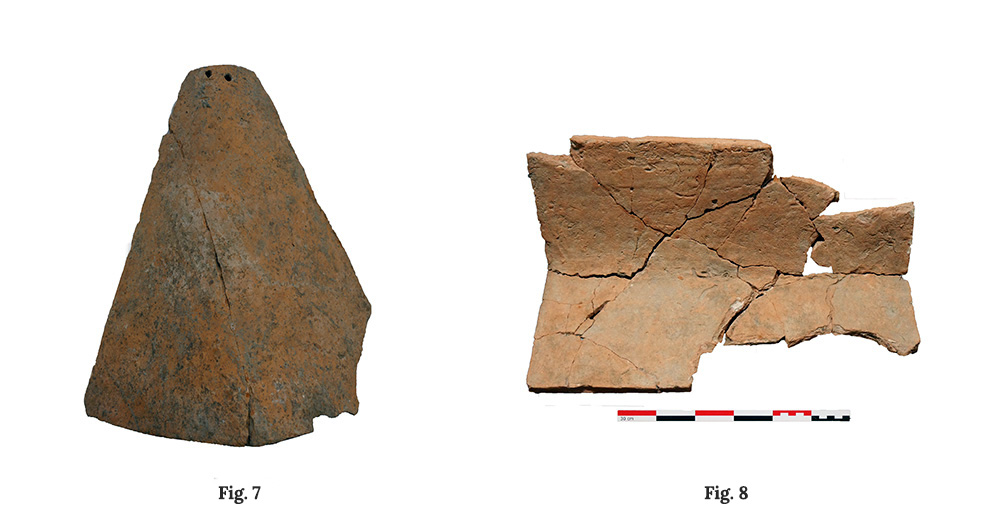

Both monks and lay brothers, whether at Preuilly or in the abbey’s various granges, produced everything necessary for the upkeep of the monastery: this includes floor tiles, roofing tiles (figs. 7 and 8), and tiles used to protect drainage pipes (figs. 9 and 10).

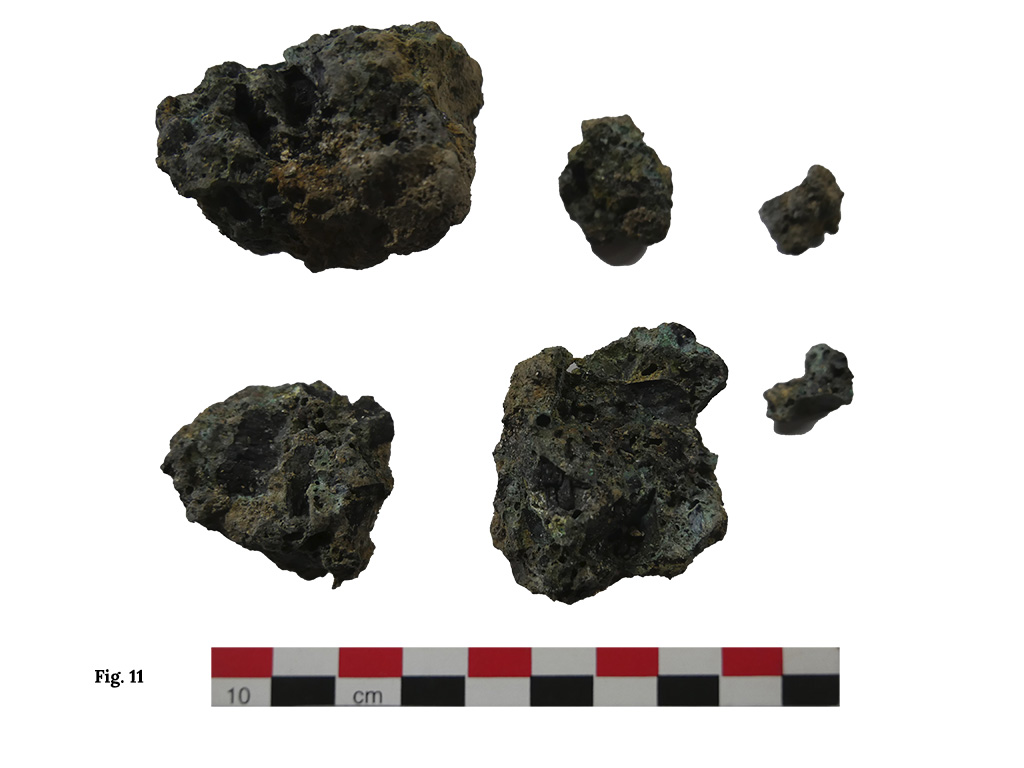

Iron, produced on nearby estates, was processed on-site, as shown by the numerous slag remains uncovered during the excavations (fig. 11).

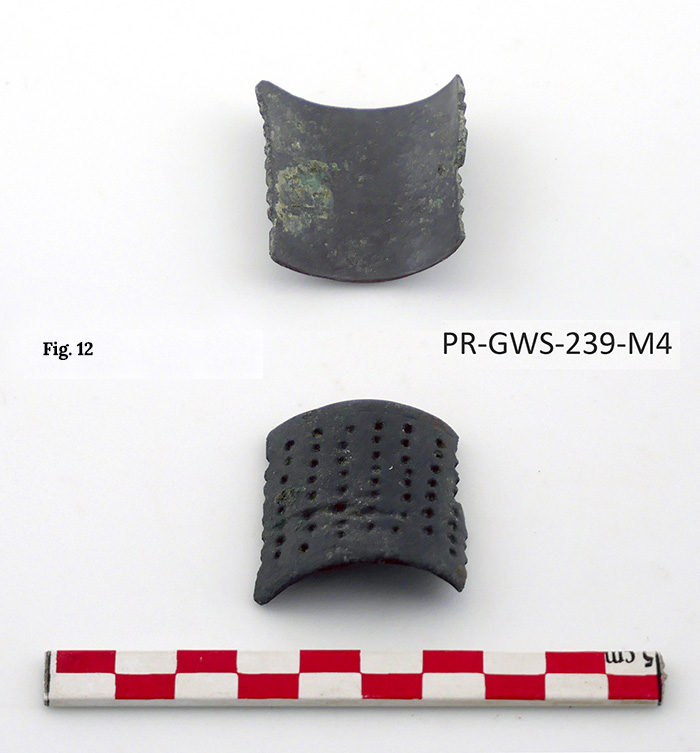

All daily tasks were performed within the monastery—sewing, for example, as evidenced by this open thimble (fig. 12). Many other remains attest to everyday life, such as fragments of high-quality pottery and glassware (fig. 13).

Nonetheless, abbots and lay benefactors received special recognition appropriate to their status. For the abbots, this is reflected in ceremonial items linked to their role, such as the abbatial crozier (fig. 14) and medallions fixed to their gloves or mitre (figs. 15 and 16).

Fig. 14: Crozier finial found in the tomb of Jean de Chanlay. Limoges, circa 1200–1215. Paris, Louvre Museum, Department of Decorative Arts, OA 10407.

(©Marie-Cécile Bardoz, Department of Decorative Arts Documentation)

Figs. 15 and 16: Medallions found in the tomb of Jean de Chanlay, Paris, between 1280 and 1291. Paris, Louvre Museum, Department of Decorative Arts, OA 3437 and OA 3438.

(©RMB/Stéphane Maréchalle)

Their burial locations reflect their importance to the monastery: the church choir, chapter house, and cloister were the most prestigious sites. Although no original tombs remain at Preuilly today except for the sarcophagus in the niche attributed to Abbot Artaud, the first abbot of Preuilly (fig. 17) 29 funerary monuments have been documented. These include stone slabs or copper plates, mostly rectangular or trapezoidal, except for the round monument of Renard de Villethierry’s heart.

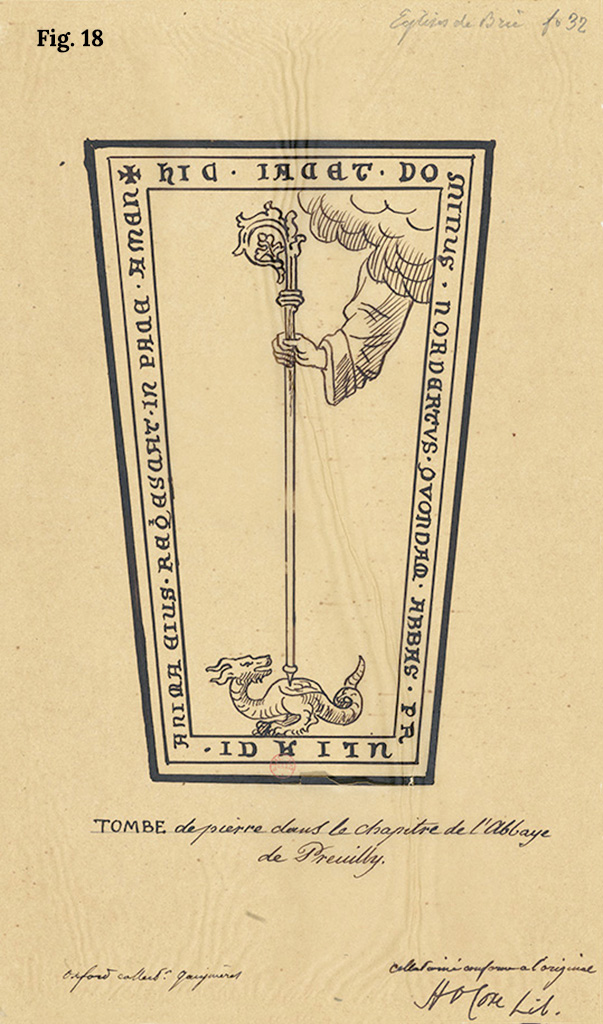

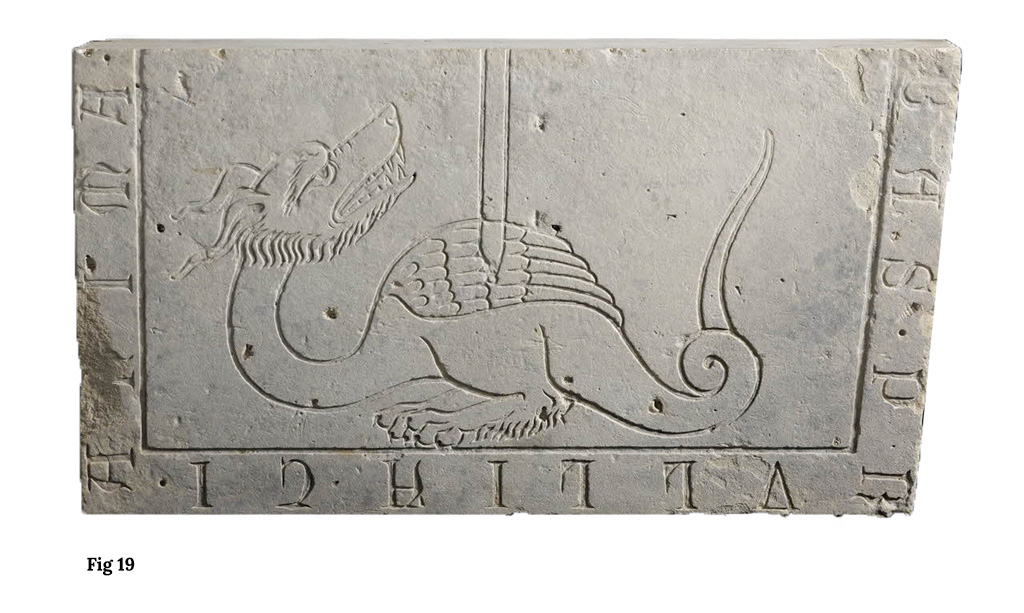

The tombs have now disappeared, but we have preserved drawings made for the artist Gaignières in the late 17th or early 18th century. One such example is the funerary slab of Norbert, 15th abbot of Preuilly, buried in the chapter house. The lower part of this slab is now in the Louvre Museum (figs. 18 and 19).

Fig. 18: Funerary slab of Norbert, BnF, Est, Pe1 o, fol. 32.

Fig. 19: Lower fragment of Norbert’s funerary slab, Louvre Museum. (©RMN-Grand Palais [Louvre Museum]/Franck Raux)

Laypeople associated with the abbey were also buried within its walls—such as Henri de Paroy, whose tombstone was located in the cloister (fig. 20).

Fig. 20: Funerary slab of Henri de Paroy, BnF, Est, Rés. Pe1 o, fol. 30.